-

Two Upcoming Talks – RIDM and IDFA

- Posted on 18th Jun

- Category:

I’m here in Montreal and about to moderate a panel on Audience Engagement. Go figure, I forgot to post this here, so unless you live in Montreal, it’s too late to plan to attend, but I’ll post some follow-up comments later. Next up is a session about the Future of VOD at IDFA in Amsterdam. If you plan to attend I hope to see you there. Here’s info on the panels.

More than ever, the question of what filmmakers must do to find and engage their audience is becoming key. Funders are asking filmmakers to go beyond marketing and distribution strategies and submit creative engagement campaigns for films that will have an impact and rally the audience around a story or a cause. But what is a successful engagement strategy and when should filmmakers start planning them? How can they do so in a way that will not only be relevant to funders but that will also contribute to a meaningful development of their film’s audience? This session will invite filmmakers to think outside the box and consider new approaches and ways of imagining the role of the viewer in the development, production and distribution phases of documentary films. It will explore the shift from audience as passive consumers to active collaborators.

GUESTS: Christopher Allen, Union Docs; Amaury Augé, Association du Cinéma Indépendant pour sa diffusion (ACID); Caitlin Boyle, Film Sprout; Catalina Briceno, Canada Media Fund; Hajnal Molnar-Szakacs, Sundance Institute

IDFA – The Future of VOD What’s in it for the Filmmaker?

Different VOD platforms, aggregators, subsidized or commercial with various business models around one table. How do they operate? And how can you, as a filmmaker or producer, benefit from them? VOD expert Brian Newman leads you through this jungle of companies that all have their own vision of the future.

Guests: Greg Rubidge (Syndicado) | Robert Franke (Viewster) | Peter Gerard (Distrify) | Casey Pugh (VHX)

-

Hollow: An Interactive Doc, launches June 20

- Posted on 14th Jun

- Category:

I’ve been following this project for a long time now, and am glad to see it finally coming out soon. On June 20th, Elaine McMillion and team will be launching a new type of doc – an online only, interactive, participatory doc experience called Hollow. From the press release:

Hollow explores the issues of small-town America through the voices and ideas of people living in McDowell County, W.Va., will launch June 20 West Virginia’s 150th statehood celebration. The immersive, online experience will combine video portraits, user-generated content, data, grassroots mapping and soundscapes on an HTML5 site and an accompanying community tool to tell the story of those living in boom-and-bust areas in small-town America.

“Hollow is an evolving story and allows the residents to update their stories to the many viewers online. This type of format provides a lean-forward and lean-back experience that both engages the user and allows them to be told a story,” McMillion said.

The interactive documentary allows users to experience the stories of over 30 residents, captures user-input data and provides story updates to featured community members through an embedded WordPress site.

I’m looking forward to checking it ou soon and hope it’s as ground-breaking as I suspect it might just be. -

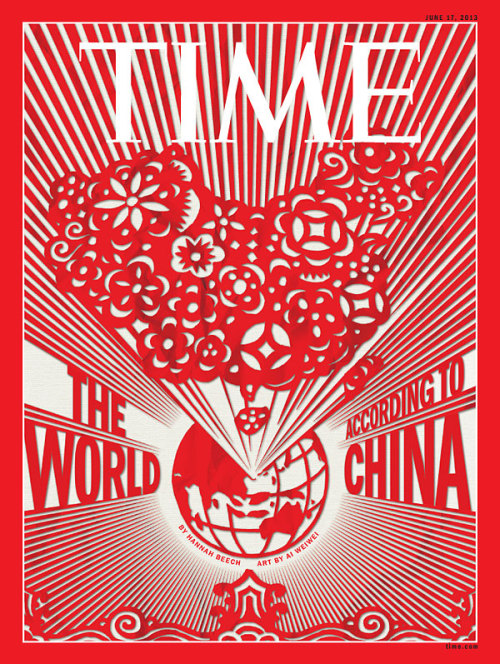

From Time, a great new cover from Ai Weiwei – and check out the…

- Posted on 7th Jun

- Category:

From Time, a great new cover from Ai Weiwei – and check out the film too!

This week’s TIME cover story, which is illustrated by the artist-activist Ai Weiwei, examines China’s place in the world.

Read a preview of the story here.

(Art by Ai Weiwei for TIME, Typography by Post Typography) -

Simple Math

- Posted on 30th May

- Category:

It isn’t magic. At the end of the day, the math for filmmakers (and distributors and other artists) is pretty simple:

You can either spend a lot on marketing or slowly build a base of fans.

But you must do the second one early and it takes a lot of hard work. It can’t be bought. Social marketing never works from scratch even with a big budget (although as Psy shows, money helps a lot).

This seems simple enough, perhaps too simple to share. But I get calls and emails from filmmakers and artists, as well as big companies, all the time about this. They think they can just start marketing something on Facebook or Twitter and win. But they can’t, because they haven’t built that base of fans. They have to spend dollars instead. And all the time, I hear from filmmakers that social doesn’t work, you have to be Kevin Smith or that Eddie Burns is just lucky. But that’s not it. They did the hard work. They built their fan base, and it works.

-

Innovation for Fests Part Two – New Models

- Posted on 14th May

- Category:

Yesterday I proposed: So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. Today, here are some thoughts and ideas:

First, curation matters. Yes, we all profess to know this…because we all think we’re curators. But we’re not. Curators are a rarefied breed who would never define curation as the act of bringing something someone else curated somewhere else to their own town. That’s programming. It’s valuable. But we need curators. Attempting good curation is as much as a risk as making good art. You might fail miserably, and you can’t blame it on someone else. Curation is a statement that stands out from the crowd. I can count the festival programmers who are also curators in North America and Europe on 10 fingers while holding a pencil. I am not qualified outside of that limited purview, but I bet my toes will suffice for the world. We need risk, experimentation, new ideas and you should count on pissing off as many people as you please. Not an easy task for a small fest selling tickets based on the reviews of some asshole who majored in journalism or film studies because other options weren’t open to them (I count myself in this group, life is harsh). But hey, you have one life to live and none after, so get to work.

Second, what matters now more than even curation is authenticity and experience. Festivals should refuse to play any film where the director, subject or someone important from the film can’t be available for a Q&A, panel or other experience; unless that film is so ground-breaking, controversial or mind-expanding, or small AND (this is crucial, and not or) it will never play in your town or on tv or on-demand unless you bring it. It will disappear to anyone of average intelligence in your community if you don’t support it. I hate to admit it, but Hollywood blockbusters count positively in this experience. If you can bring Iron Man Twenty to town with stars, or a director or even the f-n gaffer, you have an experience that will open your donor’s wallets. If you don’t, there’s no excuse to show it anyway. In spite of programmer’s protestations to the contrary, no one has ever stumbled out of a Hollywood film and discovered that avant-garde gem. Ever. While we’re at it, unless your festival is a major market, you should spend zero dollars bringing in industry reps, and reallocate those to filmmaker travel and services. Pick your keynote speaker and panelists from filmmakers and producers you bring in. Let the industry take care of itself, they aren’t that valuable to your local filmmakers, who they avoid like the plague at every party, and they are getting plenty of value from you showing their films anyway.

Next up, and related: instead of continuing to suck up to the industry that is extracting all of their value, festivals should focus more attention on those artists who, like festivals, are building their own audience. Yes, this means reaching out to Freddie Wong instead of sucking up to that foreign sales agent who might deign to give you their foreign film with no real audience for a rental of $1000 vs 50% of your box office. Forgo the meeting in Cannes and get on Skype with someone who really matters instead.

Fourth, as you might have heard, data is the new gold. I’d add to that audience aggregation. Knowing who the audience is, where they are, what they like and having a means by which to reach them. Festivals excel at getting good audiences, and good ones have built them over time. Back when B-Side existed, they ran Festival Genius, which powered the websites of numerous festivals and gave them that golden data. Perhaps they were ahead of their time, as they’ve now disappeared, but most festivals haven’t replicated their model of getting and holding onto that data. Festivals should put some effort into data aggregation – with all the proper privacy controls, of course – and they should share what data they can with the filmmakers who attend their festival. Audience award ballot scores are a good place to start. Every festival collects them, but most throw that data away after determining the winner. Geo-location of ticket buyers – hey, guess what, 90% of your audience came from Kalamazoo, perhaps you should do a screening there in the future. There’s a lot of data that could be helpful without getting too icky or breaking any privacy taboos.

Fifth, we need new business models. For at least twenty years, every festival has had the same business model and the most radical suggestion of all is that perhaps they pay filmmakers for the privilege of showing their films. I’ve come out against that proposal, because if the best we can do is offer a percentage of sales to a small audience, why bother? I could name a thousand new models, and I’m not too bright, but here’s one: how about you let filmmakers sell popcorn outside on the curb with their DVD inside the box for $10 bucks. You may think I’m joking, but truth be told, more money is made at any single screening from popcorn sales than from ticket sales. A lemonade stand may make more sense than a DVD offering at most festivals. But wait, that would take away another revenue stream from someone other than the filmmaker. Still, that would be $8+ of profit per customer! Know what the problem with that one is? Tell a filmmaker you’ll show their film to 100 people for no profit, and they’ll show up on their own dime and go to the bar during their screening. Tell them they can sell a 15 cent product for a 1000 times margin during their show and they’ll complain that you want them to work. Can’t win here… so, okay, yes, I jest. But only to show how pathetic our attempts at thinking about new business models are at this point. People talk about VOD offerings, DVD sales, ongoing curation, new fandangled shit. I won’t run the numbers, but if I had to bet on a future for indie filmmakers, it would be in fancy popcorn monopolies. Point is: there are thousands of possible ways to re-think the business model. Let’s try just one sometime.

Here’s a few more business model ideas to think about:

- Extending the online connection through year-round curation. Help your local fans discover new content year-round, not just the films that played your fest (and that’s a start for most fests), but by recommending films you love throughout the year. Help filmmakers re-connect to their audiences, push digital sales, feature regional filmmakers on your site. Perhaps you can help filmmaker with pre-sales, while selling tickets to their films. An audience member could pay one price for a fest ticket and a DVD or download and you could keep a small percentage (5%) of that sale, pushing the rest to the filmmaker. As more and more people discover and watch their entertainment online, festivals would do well to build a more interesting online presence. Few, if any, have a good year round presence and this is a golden, currently wasted, opportunity.

- Build more festival partnerships. This always gets talked about, but it’s hard work, so very few people do it. Sundance does it a little bit with some regional fests and theaters as well, but we need more festivals working together to bring filmmakers on tour, to share expenses of rentals, to share data, to build regional audiences. Help filmmakers turn a regional festival play into a tour that can actually return revenue. Heck, five fests could agree to all show the same films, one chosen by each, and let the filmmaker keep a cut, sell DVDs, etc.

- Experiment with on-demand screenings. Tugg, Gathr and others are building interesting on-demand models. Too few fests do this. I’d love to see a festival have a few slots that don’t get programmed until the last minute and it’s based on online demand, or even just switching theaters based on such demand. I know how hard slotting can be, but I still see too many films play to small audiences in a big theater at the same time that another theater is overflowing across town.

- Show more work that originates online. A serialized feature with thousands or even millions of views can still fill a theater if you get the filmmaker in attendance. Tribeca did a great job with showing Casey Pugh’s “Star Wars Uncut” this year, in a new, interactive format. This should be traveling around the country. Vimeo has done a great job with their festival of online work, but we need more of this.

- Build in more participatory experiences. People want to be part of content today. You can see it in everything from remix to machinima to the Harlem Shake. Not every festival can come up with something that isn’t too gimmicky, but it doesn’t have to be high-touch. Just helping encourage greater interaction among your audience can help. Instead of cutting off that Q&A after two questions, line-up a coffee talk next door where your filmmaker can talk in depth with those who want to hear more. Suggest local businesses where a local expert on a film’s subject might be continuing the conversation over dinner. These can be volunteer run, done through meet-up and a lot of them will fail, but we do need to give more opportunities for further engagement to those who want it.

Look, I’ll admit that none of these ideas are ground-breaking, and many aren’t going to work. I don’t have all the answers, but I think we all need to be asking a lot of questions. I see plenty of people suggesting how filmmakers and distributors need to build new business models, but fests need to do it just as much, if not more. There are a lot of really good festivals, both big and small out there, and many are doing tons of great work for very little money. Many are volunteer run, and it’s very hard to innovate when you’re just trying to break-even. I understand that, and I’m not denying here that many fests are doing a great job. But that doesn’t mean we can’t dream up new models that may work better for everyone. Our number one goal should be two-sided: helping filmmakers by better connecting them to a well-served audience. Festivals are best positioned to help move this forward, if they think creatively about these new models.

-

In my last post about film festivals, I argued that film fests needed to think about innovation (and avoid over-professionalization). Innovation is a word that gets bandied around a lot these days. We’ve seen a fair bit of innovation in certain sectors of the industry. Filmmakers are using new tools to innovate in production, storytelling, editing and even in distribution. We’ve got new models for funding, such as Kickstarter. We have new tools for measuring the impact of our films. We have new business relationships with brands. Heck, we can even make and distribute a new style of media in just six seconds via Vine, innovating the entire chain of production and distribution in one fell swoop. Weirdly, however, we’ve seen very little of it in film festivals (or the organizations that support filmmakers, but that’s another post). Not that nothing has happened here – there are grants now to support innovative artistic practices, plenty of panels and workshops about innovation, some festivals tweet, we have electronic ticketing and watch screeners online, submitted via Withoutabox or on Cinando. One festival made a Vine contest, but I’d argue that just sucked the innovation out of the medium, subjecting it to the old model. For the most part, however, film fests operate business as usual. Travel to a few film festivals, from small to large, and there isn’t much variation in the form, the business model or the thinking. I’m not arguing that we should tear apart what works. As I stood in line with 500 people in a well-organized queue at Hot Docs to watch a well crafted, well projected doc, I could feel the magic of movie-going that you rarely get anymore outside of a film festival. So this isn’t a call to arms to tear down the walls or anything (and see what can go wrong with this approach here), but as I suggested in my last post, I believe the only way forward is innovation, perhaps a little less professionalization and some fresh thinking about the underlying goals of the festival. Film festivals were created for a few reasons – to help films get seen, to reward filmmakers (with esteem, not money), to serve audiences, to fill a gap, to build community, to stimulate the local economy. These are just a few of the most prominent reasons. While these are all valid reasons, I would propose we’re at a bit of a tipping point in the film world now (crisis might be too strong a word for it) and several factors combine that should make us all want to build upon the good foundation festivals have laid, and make something even better, and our focus now should be firmly on better serving filmmakers by connecting them to their audiences, in both old and new/innovative ways. Festivals don’t need to have a panel about new models. Festivals need to create the new model. But before we can explore the new model, let us first, perhaps, acknowledge some new truths that may possibly be uncomfortable, controversial and inconvenient to acknowledge. These should inform how we think about the future of film and film festivals. Truths: Too many films are being made, and this won’t ever change. 50,000+ unique titles are submitted to film festivals annually. The majority of these filmmakers don’t get paid a living wage for their art. Even those who get major grant funding, play every great fest, and perhaps even go to the Academy awards often don’t make a living for their work. Revenue is being made on the backs of this work. Broadcasters, distributors and yes, even struggling film festivals are making more money than the artists themselves. Supply and demand is helping multiple gate-keepers but not the creators of the work. Truth: The artists, most but not all of them, are our digital share-croppers. We need our films. We need them to entertain us, to educate and inspire us, and to make us feel better for all the horrible things we’ve done to the world. Much like the agrarian and industrial societies we’ve come from, someone must be exploited to keep the system moving, and here those people are the artists. We throw our festivals. The industry comes and does business, the audiences are entertained, the sponsors push their wares, money flows. But not to the artists. They might get a flight and a sponsored beer, but not much else. Truths: There are a few artists who do get paid. They seem to fall into four camps: those born rich and not in need of income; those 3% who get lucky and their films are such a success that they actually make enough to buy a house and make another film; those who get paid to teach others how to become filming share-croppers; and a small percentage of those who have taken up the entrepreneurial model and are connecting to their films directly to their audience with innovative new business strategies. This last group has the most potential for growth, and are where we should look for the disruptive innovation we need for the industry to thrive. Those who try this and succeed remain a small percentage, akin to the few lucky ones under the “old” model, but it is a growing group. Truth: We also have many new tools for discovery of films. Quite simply, it is easier now to distribute your film to and find an audience online than you could ever do through film festivals. Let’s acknowledge another fact: an online success (let’s say one million views) is more valuable than winning any film festival award, and arguably more important than an Academy award. Let’s leave that argument aside for now, however, and just admit that you no longer have to get into a film fest to get your film seen, discovered or to become a success. Truth: online festivals don’t seem to work. They generally suck, in fact. We can’t rely just on online success either – there are plenty of people who still enjoy the theater, and who stand in line for hours to see a film at a film festival. There’s a role for film festivals, but it will be a shame if they solve that conundrum without also benefitting artists. Truth: good film festivals have built a relationship with an audience. They’ve built a brand. They are trusted sources for finding the gems out of the shit (usually) and have a team of programmers who know their audiences well (ok, just sometimes, many just program what they like). While many filmmakers are now building direct relationships with their fans, film fests can help them reach local audiences who aren’t yet fans, but might become one after discovering your film through a festival. Truth: almost no distributor has built a relationship with the audience. While some do a good job through marketing (wait, who does this? Again, another post…), for the most part they are salesmen sucking value out of the work artists and festivals do, returning little value back. The exceptions are few: some educational distributors who know their audience well, but often hold back filmmakers from their consumer audience; or those like Criterion who have built brands that add value to already great content, but this has mainly built niche audiences for very specialized films. Truth: In a world of abundance, several things become more valuable. Curation becomes important to cut through the crap. Authenticity and real experience, such as seeing a filmmaker on a panel or in a Q&A become experiences worth paying for. Data becomes gold: what festivals know about audiences becomes valuable data, and aggregating audiences becomes more important. Getting attention is harder, and attention is the new scarcity, but a contained festival helps focus attention. So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. My next post will cover a few ideas for these new models. Trackbacks/Pingbacks 10 Must Read Or Watch Film Biz Articles Of 2013 | Truly Free FilmIn my last post about film festivals, I argued that film fests needed to think about innovation (and avoid over-professionalization). Innovation is a word that gets bandied around a lot these days. We’ve seen a fair bit of innovation in certain sectors of the industry. Filmmakers are using new tools to innovate in production, storytelling, editing and even in distribution. We’ve got new models for funding, such as Kickstarter. We have new tools for measuring the impact of our films. We have new business relationships with brands. Heck, we can even make and distribute a new style of media in just six seconds via Vine, innovating the entire chain of production and distribution in one fell swoop. Weirdly, however, we’ve seen very little of it in film festivals (or the organizations that support filmmakers, but that’s another post). Not that nothing has happened here – there are grants now to support innovative artistic practices, plenty of panels and workshops about innovation, some festivals tweet, we have electronic ticketing and watch screeners online, submitted via Withoutabox or on Cinando. One festival made a Vine contest, but I’d argue that just sucked the innovation out of the medium, subjecting it to the old model. For the most part, however, film fests operate business as usual. Travel to a few film festivals, from small to large, and there isn’t much variation in the form, the business model or the thinking. I’m not arguing that we should tear apart what works. As I stood in line with 500 people in a well-organized queue at Hot Docs to watch a well crafted, well projected doc, I could feel the magic of movie-going that you rarely get anymore outside of a film festival. So this isn’t a call to arms to tear down the walls or anything (and see what can go wrong with this approach here), but as I suggested in my last post, I believe the only way forward is innovation, perhaps a little less professionalization and some fresh thinking about the underlying goals of the festival. Film festivals were created for a few reasons – to help films get seen, to reward filmmakers (with esteem, not money), to serve audiences, to fill a gap, to build community, to stimulate the local economy. These are just a few of the most prominent reasons. While these are all valid reasons, I would propose we’re at a bit of a tipping point in the film world now (crisis might be too strong a word for it) and several factors combine that should make us all want to build upon the good foundation festivals have laid, and make something even better, and our focus now should be firmly on better serving filmmakers by connecting them to their audiences, in both old and new/innovative ways. Festivals don’t need to have a panel about new models. Festivals need to create the new model. But before we can explore the new model, let us first, perhaps, acknowledge some new truths that may possibly be uncomfortable, controversial and inconvenient to acknowledge. These should inform how we think about the future of film and film festivals. Truths: Too many films are being made, and this won’t ever change. 50,000+ unique titles are submitted to film festivals annually. The majority of these filmmakers don’t get paid a living wage for their art. Even those who get major grant funding, play every great fest, and perhaps even go to the Academy awards often don’t make a living for their work. Revenue is being made on the backs of this work. Broadcasters, distributors and yes, even struggling film festivals are making more money than the artists themselves. Supply and demand is helping multiple gate-keepers but not the creators of the work. Truth: The artists, most but not all of them, are our digital share-croppers. We need our films. We need them to entertain us, to educate and inspire us, and to make us feel better for all the horrible things we’ve done to the world. Much like the agrarian and industrial societies we’ve come from, someone must be exploited to keep the system moving, and here those people are the artists. We throw our festivals. The industry comes and does business, the audiences are entertained, the sponsors push their wares, money flows. But not to the artists. They might get a flight and a sponsored beer, but not much else. Truths: There are a few artists who do get paid. They seem to fall into four camps: those born rich and not in need of income; those 3% who get lucky and their films are such a success that they actually make enough to buy a house and make another film; those who get paid to teach others how to become filming share-croppers; and a small percentage of those who have taken up the entrepreneurial model and are connecting to their films directly to their audience with innovative new business strategies. This last group has the most potential for growth, and are where we should look for the disruptive innovation we need for the industry to thrive. Those who try this and succeed remain a small percentage, akin to the few lucky ones under the “old” model, but it is a growing group. Truth: We also have many new tools for discovery of films. Quite simply, it is easier now to distribute your film to and find an audience online than you could ever do through film festivals. Let’s acknowledge another fact: an online success (let’s say one million views) is more valuable than winning any film festival award, and arguably more important than an Academy award. Let’s leave that argument aside for now, however, and just admit that you no longer have to get into a film fest to get your film seen, discovered or to become a success. Truth: online festivals don’t seem to work. They generally suck, in fact. We can’t rely just on online success either – there are plenty of people who still enjoy the theater, and who stand in line for hours to see a film at a film festival. There’s a role for film festivals, but it will be a shame if they solve that conundrum without also benefitting artists. Truth: good film festivals have built a relationship with an audience. They’ve built a brand. They are trusted sources for finding the gems out of the shit (usually) and have a team of programmers who know their audiences well (ok, just sometimes, many just program what they like). While many filmmakers are now building direct relationships with their fans, film fests can help them reach local audiences who aren’t yet fans, but might become one after discovering your film through a festival. Truth: almost no distributor has built a relationship with the audience. While some do a good job through marketing (wait, who does this? Again, another post…), for the most part they are salesmen sucking value out of the work artists and festivals do, returning little value back. The exceptions are few: some educational distributors who know their audience well, but often hold back filmmakers from their consumer audience; or those like Criterion who have built brands that add value to already great content, but this has mainly built niche audiences for very specialized films. Truth: In a world of abundance, several things become more valuable. Curation becomes important to cut through the crap. Authenticity and real experience, such as seeing a filmmaker on a panel or in a Q&A become experiences worth paying for. Data becomes gold: what festivals know about audiences becomes valuable data, and aggregating audiences becomes more important. Getting attention is harder, and attention is the new scarcity, but a contained festival helps focus attention. So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. My next post will cover a few ideas for these new models. Trackbacks/Pingbacks 10 Must Read Or Watch Film Biz Articles Of 2013 | Truly Free FilmIn my last post about film festivals, I argued that film fests needed to think about innovation (and avoid over-professionalization). Innovation is a word that gets bandied around a lot these days. We’ve seen a fair bit of innovation in certain sectors of the industry. Filmmakers are using new tools to innovate in production, storytelling, editing and even in distribution. We’ve got new models for funding, such as Kickstarter. We have new tools for measuring the impact of our films. We have new business relationships with brands. Heck, we can even make and distribute a new style of media in just six seconds via Vine, innovating the entire chain of production and distribution in one fell swoop. Weirdly, however, we’ve seen very little of it in film festivals (or the organizations that support filmmakers, but that’s another post). Not that nothing has happened here – there are grants now to support innovative artistic practices, plenty of panels and workshops about innovation, some festivals tweet, we have electronic ticketing and watch screeners online, submitted via Withoutabox or on Cinando. One festival made a Vine contest, but I’d argue that just sucked the innovation out of the medium, subjecting it to the old model. For the most part, however, film fests operate business as usual. Travel to a few film festivals, from small to large, and there isn’t much variation in the form, the business model or the thinking. I’m not arguing that we should tear apart what works. As I stood in line with 500 people in a well-organized queue at Hot Docs to watch a well crafted, well projected doc, I could feel the magic of movie-going that you rarely get anymore outside of a film festival. So this isn’t a call to arms to tear down the walls or anything (and see what can go wrong with this approach here), but as I suggested in my last post, I believe the only way forward is innovation, perhaps a little less professionalization and some fresh thinking about the underlying goals of the festival. Film festivals were created for a few reasons – to help films get seen, to reward filmmakers (with esteem, not money), to serve audiences, to fill a gap, to build community, to stimulate the local economy. These are just a few of the most prominent reasons. While these are all valid reasons, I would propose we’re at a bit of a tipping point in the film world now (crisis might be too strong a word for it) and several factors combine that should make us all want to build upon the good foundation festivals have laid, and make something even better, and our focus now should be firmly on better serving filmmakers by connecting them to their audiences, in both old and new/innovative ways. Festivals don’t need to have a panel about new models. Festivals need to create the new model. But before we can explore the new model, let us first, perhaps, acknowledge some new truths that may possibly be uncomfortable, controversial and inconvenient to acknowledge. These should inform how we think about the future of film and film festivals. Truths: Too many films are being made, and this won’t ever change. 50,000+ unique titles are submitted to film festivals annually. The majority of these filmmakers don’t get paid a living wage for their art. Even those who get major grant funding, play every great fest, and perhaps even go to the Academy awards often don’t make a living for their work. Revenue is being made on the backs of this work. Broadcasters, distributors and yes, even struggling film festivals are making more money than the artists themselves. Supply and demand is helping multiple gate-keepers but not the creators of the work. Truth: The artists, most but not all of them, are our digital share-croppers. We need our films. We need them to entertain us, to educate and inspire us, and to make us feel better for all the horrible things we’ve done to the world. Much like the agrarian and industrial societies we’ve come from, someone must be exploited to keep the system moving, and here those people are the artists. We throw our festivals. The industry comes and does business, the audiences are entertained, the sponsors push their wares, money flows. But not to the artists. They might get a flight and a sponsored beer, but not much else. Truths: There are a few artists who do get paid. They seem to fall into four camps: those born rich and not in need of income; those 3% who get lucky and their films are such a success that they actually make enough to buy a house and make another film; those who get paid to teach others how to become filming share-croppers; and a small percentage of those who have taken up the entrepreneurial model and are connecting to their films directly to their audience with innovative new business strategies. This last group has the most potential for growth, and are where we should look for the disruptive innovation we need for the industry to thrive. Those who try this and succeed remain a small percentage, akin to the few lucky ones under the “old” model, but it is a growing group. Truth: We also have many new tools for discovery of films. Quite simply, it is easier now to distribute your film to and find an audience online than you could ever do through film festivals. Let’s acknowledge another fact: an online success (let’s say one million views) is more valuable than winning any film festival award, and arguably more important than an Academy award. Let’s leave that argument aside for now, however, and just admit that you no longer have to get into a film fest to get your film seen, discovered or to become a success. Truth: online festivals don’t seem to work. They generally suck, in fact. We can’t rely just on online success either – there are plenty of people who still enjoy the theater, and who stand in line for hours to see a film at a film festival. There’s a role for film festivals, but it will be a shame if they solve that conundrum without also benefitting artists. Truth: good film festivals have built a relationship with an audience. They’ve built a brand. They are trusted sources for finding the gems out of the shit (usually) and have a team of programmers who know their audiences well (ok, just sometimes, many just program what they like). While many filmmakers are now building direct relationships with their fans, film fests can help them reach local audiences who aren’t yet fans, but might become one after discovering your film through a festival. Truth: almost no distributor has built a relationship with the audience. While some do a good job through marketing (wait, who does this? Again, another post…), for the most part they are salesmen sucking value out of the work artists and festivals do, returning little value back. The exceptions are few: some educational distributors who know their audience well, but often hold back filmmakers from their consumer audience; or those like Criterion who have built brands that add value to already great content, but this has mainly built niche audiences for very specialized films. Truth: In a world of abundance, several things become more valuable. Curation becomes important to cut through the crap. Authenticity and real experience, such as seeing a filmmaker on a panel or in a Q&A become experiences worth paying for. Data becomes gold: what festivals know about audiences becomes valuable data, and aggregating audiences becomes more important. Getting attention is harder, and attention is the new scarcity, but a contained festival helps focus attention. So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. My next post will cover a few ideas for these new models. Trackbacks/Pingbacks 10 Must Read Or Watch Film Biz Articles Of 2013 | Truly Free FilmIn my last post about film festivals, I argued that film fests needed to think about innovation (and avoid over-professionalization). Innovation is a word that gets bandied around a lot these days. We’ve seen a fair bit of innovation in certain sectors of the industry. Filmmakers are using new tools to innovate in production, storytelling, editing and even in distribution. We’ve got new models for funding, such as Kickstarter. We have new tools for measuring the impact of our films. We have new business relationships with brands. Heck, we can even make and distribute a new style of media in just six seconds via Vine, innovating the entire chain of production and distribution in one fell swoop. Weirdly, however, we’ve seen very little of it in film festivals (or the organizations that support filmmakers, but that’s another post). Not that nothing has happened here – there are grants now to support innovative artistic practices, plenty of panels and workshops about innovation, some festivals tweet, we have electronic ticketing and watch screeners online, submitted via Withoutabox or on Cinando. One festival made a Vine contest, but I’d argue that just sucked the innovation out of the medium, subjecting it to the old model. For the most part, however, film fests operate business as usual. Travel to a few film festivals, from small to large, and there isn’t much variation in the form, the business model or the thinking. I’m not arguing that we should tear apart what works. As I stood in line with 500 people in a well-organized queue at Hot Docs to watch a well crafted, well projected doc, I could feel the magic of movie-going that you rarely get anymore outside of a film festival. So this isn’t a call to arms to tear down the walls or anything (and see what can go wrong with this approach here), but as I suggested in my last post, I believe the only way forward is innovation, perhaps a little less professionalization and some fresh thinking about the underlying goals of the festival. Film festivals were created for a few reasons – to help films get seen, to reward filmmakers (with esteem, not money), to serve audiences, to fill a gap, to build community, to stimulate the local economy. These are just a few of the most prominent reasons. While these are all valid reasons, I would propose we’re at a bit of a tipping point in the film world now (crisis might be too strong a word for it) and several factors combine that should make us all want to build upon the good foundation festivals have laid, and make something even better, and our focus now should be firmly on better serving filmmakers by connecting them to their audiences, in both old and new/innovative ways. Festivals don’t need to have a panel about new models. Festivals need to create the new model. But before we can explore the new model, let us first, perhaps, acknowledge some new truths that may possibly be uncomfortable, controversial and inconvenient to acknowledge. These should inform how we think about the future of film and film festivals. Truths: Too many films are being made, and this won’t ever change. 50,000+ unique titles are submitted to film festivals annually. The majority of these filmmakers don’t get paid a living wage for their art. Even those who get major grant funding, play every great fest, and perhaps even go to the Academy awards often don’t make a living for their work. Revenue is being made on the backs of this work. Broadcasters, distributors and yes, even struggling film festivals are making more money than the artists themselves. Supply and demand is helping multiple gate-keepers but not the creators of the work. Truth: The artists, most but not all of them, are our digital share-croppers. We need our films. We need them to entertain us, to educate and inspire us, and to make us feel better for all the horrible things we’ve done to the world. Much like the agrarian and industrial societies we’ve come from, someone must be exploited to keep the system moving, and here those people are the artists. We throw our festivals. The industry comes and does business, the audiences are entertained, the sponsors push their wares, money flows. But not to the artists. They might get a flight and a sponsored beer, but not much else. Truths: There are a few artists who do get paid. They seem to fall into four camps: those born rich and not in need of income; those 3% who get lucky and their films are such a success that they actually make enough to buy a house and make another film; those who get paid to teach others how to become filming share-croppers; and a small percentage of those who have taken up the entrepreneurial model and are connecting to their films directly to their audience with innovative new business strategies. This last group has the most potential for growth, and are where we should look for the disruptive innovation we need for the industry to thrive. Those who try this and succeed remain a small percentage, akin to the few lucky ones under the “old” model, but it is a growing group. Truth: We also have many new tools for discovery of films. Quite simply, it is easier now to distribute your film to and find an audience online than you could ever do through film festivals. Let’s acknowledge another fact: an online success (let’s say one million views) is more valuable than winning any film festival award, and arguably more important than an Academy award. Let’s leave that argument aside for now, however, and just admit that you no longer have to get into a film fest to get your film seen, discovered or to become a success. Truth: online festivals don’t seem to work. They generally suck, in fact. We can’t rely just on online success either – there are plenty of people who still enjoy the theater, and who stand in line for hours to see a film at a film festival. There’s a role for film festivals, but it will be a shame if they solve that conundrum without also benefitting artists. Truth: good film festivals have built a relationship with an audience. They’ve built a brand. They are trusted sources for finding the gems out of the shit (usually) and have a team of programmers who know their audiences well (ok, just sometimes, many just program what they like). While many filmmakers are now building direct relationships with their fans, film fests can help them reach local audiences who aren’t yet fans, but might become one after discovering your film through a festival. Truth: almost no distributor has built a relationship with the audience. While some do a good job through marketing (wait, who does this? Again, another post…), for the most part they are salesmen sucking value out of the work artists and festivals do, returning little value back. The exceptions are few: some educational distributors who know their audience well, but often hold back filmmakers from their consumer audience; or those like Criterion who have built brands that add value to already great content, but this has mainly built niche audiences for very specialized films. Truth: In a world of abundance, several things become more valuable. Curation becomes important to cut through the crap. Authenticity and real experience, such as seeing a filmmaker on a panel or in a Q&A become experiences worth paying for. Data becomes gold: what festivals know about audiences becomes valuable data, and aggregating audiences becomes more important. Getting attention is harder, and attention is the new scarcity, but a contained festival helps focus attention. So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. My next post will cover a few ideas for these new models. Trackbacks/Pingbacks 10 Must Read Or Watch Film Biz Articles Of 2013 | Truly Free FilmIn my last post about film festivals, I argued that film fests needed to think about innovation (and avoid over-professionalization). Innovation is a word that gets bandied around a lot these days. We’ve seen a fair bit of innovation in certain sectors of the industry. Filmmakers are using new tools to innovate in production, storytelling, editing and even in distribution. We’ve got new models for funding, such as Kickstarter. We have new tools for measuring the impact of our films. We have new business relationships with brands. Heck, we can even make and distribute a new style of media in just six seconds via Vine, innovating the entire chain of production and distribution in one fell swoop. Weirdly, however, we’ve seen very little of it in film festivals (or the organizations that support filmmakers, but that’s another post). Not that nothing has happened here – there are grants now to support innovative artistic practices, plenty of panels and workshops about innovation, some festivals tweet, we have electronic ticketing and watch screeners online, submitted via Withoutabox or on Cinando. One festival made a Vine contest, but I’d argue that just sucked the innovation out of the medium, subjecting it to the old model. For the most part, however, film fests operate business as usual. Travel to a few film festivals, from small to large, and there isn’t much variation in the form, the business model or the thinking. I’m not arguing that we should tear apart what works. As I stood in line with 500 people in a well-organized queue at Hot Docs to watch a well crafted, well projected doc, I could feel the magic of movie-going that you rarely get anymore outside of a film festival. So this isn’t a call to arms to tear down the walls or anything (and see what can go wrong with this approach here), but as I suggested in my last post, I believe the only way forward is innovation, perhaps a little less professionalization and some fresh thinking about the underlying goals of the festival. Film festivals were created for a few reasons – to help films get seen, to reward filmmakers (with esteem, not money), to serve audiences, to fill a gap, to build community, to stimulate the local economy. These are just a few of the most prominent reasons. While these are all valid reasons, I would propose we’re at a bit of a tipping point in the film world now (crisis might be too strong a word for it) and several factors combine that should make us all want to build upon the good foundation festivals have laid, and make something even better, and our focus now should be firmly on better serving filmmakers by connecting them to their audiences, in both old and new/innovative ways. Festivals don’t need to have a panel about new models. Festivals need to create the new model. But before we can explore the new model, let us first, perhaps, acknowledge some new truths that may possibly be uncomfortable, controversial and inconvenient to acknowledge. These should inform how we think about the future of film and film festivals. Truths: Too many films are being made, and this won’t ever change. 50,000+ unique titles are submitted to film festivals annually. The majority of these filmmakers don’t get paid a living wage for their art. Even those who get major grant funding, play every great fest, and perhaps even go to the Academy awards often don’t make a living for their work. Revenue is being made on the backs of this work. Broadcasters, distributors and yes, even struggling film festivals are making more money than the artists themselves. Supply and demand is helping multiple gate-keepers but not the creators of the work. Truth: The artists, most but not all of them, are our digital share-croppers. We need our films. We need them to entertain us, to educate and inspire us, and to make us feel better for all the horrible things we’ve done to the world. Much like the agrarian and industrial societies we’ve come from, someone must be exploited to keep the system moving, and here those people are the artists. We throw our festivals. The industry comes and does business, the audiences are entertained, the sponsors push their wares, money flows. But not to the artists. They might get a flight and a sponsored beer, but not much else. Truths: There are a few artists who do get paid. They seem to fall into four camps: those born rich and not in need of income; those 3% who get lucky and their films are such a success that they actually make enough to buy a house and make another film; those who get paid to teach others how to become filming share-croppers; and a small percentage of those who have taken up the entrepreneurial model and are connecting to their films directly to their audience with innovative new business strategies. This last group has the most potential for growth, and are where we should look for the disruptive innovation we need for the industry to thrive. Those who try this and succeed remain a small percentage, akin to the few lucky ones under the “old” model, but it is a growing group. Truth: We also have many new tools for discovery of films. Quite simply, it is easier now to distribute your film to and find an audience online than you could ever do through film festivals. Let’s acknowledge another fact: an online success (let’s say one million views) is more valuable than winning any film festival award, and arguably more important than an Academy award. Let’s leave that argument aside for now, however, and just admit that you no longer have to get into a film fest to get your film seen, discovered or to become a success. Truth: online festivals don’t seem to work. They generally suck, in fact. We can’t rely just on online success either – there are plenty of people who still enjoy the theater, and who stand in line for hours to see a film at a film festival. There’s a role for film festivals, but it will be a shame if they solve that conundrum without also benefitting artists. Truth: good film festivals have built a relationship with an audience. They’ve built a brand. They are trusted sources for finding the gems out of the shit (usually) and have a team of programmers who know their audiences well (ok, just sometimes, many just program what they like). While many filmmakers are now building direct relationships with their fans, film fests can help them reach local audiences who aren’t yet fans, but might become one after discovering your film through a festival. Truth: almost no distributor has built a relationship with the audience. While some do a good job through marketing (wait, who does this? Again, another post…), for the most part they are salesmen sucking value out of the work artists and festivals do, returning little value back. The exceptions are few: some educational distributors who know their audience well, but often hold back filmmakers from their consumer audience; or those like Criterion who have built brands that add value to already great content, but this has mainly built niche audiences for very specialized films. Truth: In a world of abundance, several things become more valuable. Curation becomes important to cut through the crap. Authenticity and real experience, such as seeing a filmmaker on a panel or in a Q&A become experiences worth paying for. Data becomes gold: what festivals know about audiences becomes valuable data, and aggregating audiences becomes more important. Getting attention is harder, and attention is the new scarcity, but a contained festival helps focus attention. So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. My next post will cover a few ideas for these new models. Trackbacks/Pingbacks 10 Must Read Or Watch Film Biz Articles Of 2013 | Truly Free FilmIn my last post about film festivals, I argued that film fests needed to think about innovation (and avoid over-professionalization). Innovation is a word that gets bandied around a lot these days. We’ve seen a fair bit of innovation in certain sectors of the industry. Filmmakers are using new tools to innovate in production, storytelling, editing and even in distribution. We’ve got new models for funding, such as Kickstarter. We have new tools for measuring the impact of our films. We have new business relationships with brands. Heck, we can even make and distribute a new style of media in just six seconds via Vine, innovating the entire chain of production and distribution in one fell swoop. Weirdly, however, we’ve seen very little of it in film festivals (or the organizations that support filmmakers, but that’s another post). Not that nothing has happened here – there are grants now to support innovative artistic practices, plenty of panels and workshops about innovation, some festivals tweet, we have electronic ticketing and watch screeners online, submitted via Withoutabox or on Cinando. One festival made a Vine contest, but I’d argue that just sucked the innovation out of the medium, subjecting it to the old model. For the most part, however, film fests operate business as usual. Travel to a few film festivals, from small to large, and there isn’t much variation in the form, the business model or the thinking. I’m not arguing that we should tear apart what works. As I stood in line with 500 people in a well-organized queue at Hot Docs to watch a well crafted, well projected doc, I could feel the magic of movie-going that you rarely get anymore outside of a film festival. So this isn’t a call to arms to tear down the walls or anything (and see what can go wrong with this approach here), but as I suggested in my last post, I believe the only way forward is innovation, perhaps a little less professionalization and some fresh thinking about the underlying goals of the festival. Film festivals were created for a few reasons – to help films get seen, to reward filmmakers (with esteem, not money), to serve audiences, to fill a gap, to build community, to stimulate the local economy. These are just a few of the most prominent reasons. While these are all valid reasons, I would propose we’re at a bit of a tipping point in the film world now (crisis might be too strong a word for it) and several factors combine that should make us all want to build upon the good foundation festivals have laid, and make something even better, and our focus now should be firmly on better serving filmmakers by connecting them to their audiences, in both old and new/innovative ways. Festivals don’t need to have a panel about new models. Festivals need to create the new model. But before we can explore the new model, let us first, perhaps, acknowledge some new truths that may possibly be uncomfortable, controversial and inconvenient to acknowledge. These should inform how we think about the future of film and film festivals. Truths: Too many films are being made, and this won’t ever change. 50,000+ unique titles are submitted to film festivals annually. The majority of these filmmakers don’t get paid a living wage for their art. Even those who get major grant funding, play every great fest, and perhaps even go to the Academy awards often don’t make a living for their work. Revenue is being made on the backs of this work. Broadcasters, distributors and yes, even struggling film festivals are making more money than the artists themselves. Supply and demand is helping multiple gate-keepers but not the creators of the work. Truth: The artists, most but not all of them, are our digital share-croppers. We need our films. We need them to entertain us, to educate and inspire us, and to make us feel better for all the horrible things we’ve done to the world. Much like the agrarian and industrial societies we’ve come from, someone must be exploited to keep the system moving, and here those people are the artists. We throw our festivals. The industry comes and does business, the audiences are entertained, the sponsors push their wares, money flows. But not to the artists. They might get a flight and a sponsored beer, but not much else. Truths: There are a few artists who do get paid. They seem to fall into four camps: those born rich and not in need of income; those 3% who get lucky and their films are such a success that they actually make enough to buy a house and make another film; those who get paid to teach others how to become filming share-croppers; and a small percentage of those who have taken up the entrepreneurial model and are connecting to their films directly to their audience with innovative new business strategies. This last group has the most potential for growth, and are where we should look for the disruptive innovation we need for the industry to thrive. Those who try this and succeed remain a small percentage, akin to the few lucky ones under the “old” model, but it is a growing group. Truth: We also have many new tools for discovery of films. Quite simply, it is easier now to distribute your film to and find an audience online than you could ever do through film festivals. Let’s acknowledge another fact: an online success (let’s say one million views) is more valuable than winning any film festival award, and arguably more important than an Academy award. Let’s leave that argument aside for now, however, and just admit that you no longer have to get into a film fest to get your film seen, discovered or to become a success. Truth: online festivals don’t seem to work. They generally suck, in fact. We can’t rely just on online success either – there are plenty of people who still enjoy the theater, and who stand in line for hours to see a film at a film festival. There’s a role for film festivals, but it will be a shame if they solve that conundrum without also benefitting artists. Truth: good film festivals have built a relationship with an audience. They’ve built a brand. They are trusted sources for finding the gems out of the shit (usually) and have a team of programmers who know their audiences well (ok, just sometimes, many just program what they like). While many filmmakers are now building direct relationships with their fans, film fests can help them reach local audiences who aren’t yet fans, but might become one after discovering your film through a festival. Truth: almost no distributor has built a relationship with the audience. While some do a good job through marketing (wait, who does this? Again, another post…), for the most part they are salesmen sucking value out of the work artists and festivals do, returning little value back. The exceptions are few: some educational distributors who know their audience well, but often hold back filmmakers from their consumer audience; or those like Criterion who have built brands that add value to already great content, but this has mainly built niche audiences for very specialized films. Truth: In a world of abundance, several things become more valuable. Curation becomes important to cut through the crap. Authenticity and real experience, such as seeing a filmmaker on a panel or in a Q&A become experiences worth paying for. Data becomes gold: what festivals know about audiences becomes valuable data, and aggregating audiences becomes more important. Getting attention is harder, and attention is the new scarcity, but a contained festival helps focus attention. So given all of these new truths, and what we seem to know about the new realities of how the web works, how video online works and where things seem to be headed it would seem we can make some guesses as to ways in which film fests might innovate, and quite possibly help both filmmakers and audiences in the process. My next post will cover a few ideas for these new models. Trackbacks/Pingbacks 10 Must Read Or Watch Film Biz Articles Of 2013 | Truly Free Film

Innovating the New Model in Film Fests

- Posted on 13th May

- Category:

-

Flicklist at San Francisco Film Fest’s A2E Launchpad

- Posted on 13th May

- Category:

On May 3rd and 4th, I’ll be taking part in the San Francisco Film Fest’s new A2E Launchpad, with Flicklist. Our app has been quite slow to launch, but we’re in private beta and moving to public soon, and quite appropriately, we’re doing it by talking to filmmakers about how they can use Flicklist to connect to audiences.

A2E is a new initiative from the SFFS now that Ted Hope has taken over- and he’s a partner in Flicklist, so we thought it would be the perfect place to talk about this new venture. The line-up looks great. Here’s more info from their site:

“The cinematic landscape has changed – there are virtually no barriers to access and our increasingly fragmented audiences are faced with an overwhelming abundance of content. This new landscape needs new tools, strategies and practices and the San Francisco Film Society is focused on helping artists, audiences, investors and industry navigate the emerging terrain.

A2E is intent on providing artists with entrepreneurial skills. Led by San Francisco Film Society Executive Director and indie film veteran Ted Hope, pioneers of independent film’s digital era will join forces this under this banner of programming to plot our bright future.

A2E explores what can happen when we bring an abundance of talent, imagination and expertise together.

A2E is where storytelling and entrepreneurial culture intersect. A2E builds upon San Francisco’s culture of innovation utilizing Silicon Valley’s philosophy in order to succeed: fail fast, fail often, share the results.”

There’s some great companies taking part too: Vimeo, Fandor, Assemble and more. Check out the full list at the SFFS website, and contact me if you’ll be there and want to learn more about Flicklist.

-

Shored Up at Montclair

- Posted on 23rd Apr

- Category:

For the past several months, I’ve been working as an executive producer on the new film Shored Up by Benjamin Kalina. The film is set to premiere at the fantastic Montclair Film Festival in New Jersey on May 5th at 3pm. If you live in NYC or nearby, it’s quite easy to get to and there are many great films showing in addition to ours. Buy tickets here, and check out the trailer below.

We hope you can attend the premiere!

-

Hyper-Professionalization and Atrophy in Indie Film

- Posted on 19th Mar

- Category:

Yesterday in IndieWire, and not long ago here, I spoke briefly to the idea of what questions we should be asking about film festivals and how they might best help filmmakers. Before speaking further to some of these solutions, I want to explore another problem that keeps rattling around in my brain and that I think is interconnected. My worry about the current state of film fests is inter-related with what I think is a bigger problem. Indie and Arthouse film have become hyper-professionalized, and like so many art forms, this often leads to stagnation, atrophy even, and misaligned artistic practice, with art being subservient to satisfying the needs of the bureaucratic and commercial status-quos.

Film festivals, which almost universally in the United States started small and volunteer- run, have bureaucratized to the point where they’ve converged into a monotonous mass – same sponsors, identical films, universal philosophy and a consistent appeal to regional bonhomie at the expense of true artistic integrity, chance of experimentation, real community building or, god-forbid, actual character. Yes, each has its local quirks and some program a parade or some other side-show to keep the indie spirit, and most are fun to drink and carouse at, but it remains possible to travel from show to show, wondering which city you’re in, how their programming is different and why you’re being driven around in this Chevy Suburban, sponsor of the Environmental Film strand? The zenith of this trend is now evidenced by not one, but two separate bodies trying to organize, professionalize (we do live in redundancy land here) and create an overarching trade organization, proof positive of the ossification of the field.

The funding, and thus creation, of film has reached this same professional saturation point. Many docs are now funded through sophisticated investment pools, where consensus on return on dual investment (social and dollar value created) determines what gets funded. All other funders being professionalized, and thus inter-related by issues of class, belonging and power, this leads to the same types of films being funded and created, and a herd mentality of support beneficial to the recipients but detrimental to the chaos, experimentation and serendipity needed for the field to avoid stagnation. What you see at Sundance, on PBS, VOD or in theaters is being increasingly dictated by the predilections and predispositions of these interconnected funders, and ultimately pre-determined for the viewer based on criteria other than the artistic judgment of the audience, those proletariat to be engaged, activated and urged towards changing the world.

Foundations, ever ready to professionalize their subjects and always already at the top of this hierarchy, lead the field from trend to trend, today’s transmedia funding being yesterday’s youth media – the holy grail preached and reached for by all, until the money shifts course again. Foundation funding for artistic filmmaking devoid of social issues, while never abundant, has been reduced to just two, perhaps three, funders. The gates to their ivory towers, ever-guarded, are now encircled by more middle-men known as re-grant organizations, who take their cut to pay for the professionalized overhead needed to ensure quality control. The recipients of their largesse are increasingly homogenized as well, support from investors and philanthropy intertwined throughout the supply chain, ensuring a uniform product.

Skip on over to the narrative funding world, and find that you can now track and follow the latest projects via online investment communities (such as Slated, of which I am a member), pre-vetted, controlled and ever-professionalized. Even that democratized arena of fundraising known as crowd-funding is undergoing concurrent movements towards both governmental oversight to allow further professionalization (the JOBS Act) as well as a general movement where one is not a success unless they’ve beaten a Kickstarter record, identified their core fans before shooting and have generally conformed to the new orthodoxy of how to fund and create a film. With Veronica Mars now being Kickstarted, for a major studio, we can expect even more calls for professionalization of the process.

None of this would be a problem; in fact I can argue how great it is in this same breath, except for what’s occurring isn’t good for the long-term health of the field. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. None of the persons working in this arena have anything but the highest ideals and standards. As Ray McKinnon says in the Academy winning short film, The Accountant, “If a man builds a machine and that machine conspires with a machine built by another man, are those men conspiring?” The drive towards hyper-professionalization is pushed by people trying to grow up and build a better system. The dream probably remains the same for each of them; it’s a dream I’ve dreamt before myself – to build an infrastructure that can support great art and bring it to audiences, to have a greater impact and live a comfortable life in support of the arts. These are all laudable goals to be sure.

Unfortunately, we have ample evidence that infrastructure supports infrastructure, and that stability squeezes out anything that may buck the status quo. MoMA is a sanitized realm for a reason. Wynton Marsalis preaches a certain gospel of Jazz at Lincoln Center (dismissive of experimentation and driven by a grand narrative) to the exclusion of other possibilities. The machine breeds more machines, produces machine-made art, devoid of imperfection and chance. A certain level of professionalism must be achieved to even communicate with the machine. Classical music and Opera are the extremes of this drive, but their model is the only end-point to this path. All of these places exhibit great art, but none drive culture and push society as they have and should. I’m not arguing they aren’t good and valuable, mind you, but that we don’t want independent/artistic film to become just this.

If we want independent/artistic film to remain vibrant and an active provocateur of culture, as opposed to becoming a well-made museum piece, we need to resist the urge towards hyper-professionalism. We need to replace it with innovation and imperfection.

How do we do this? That’s a question I hope to begin to address in my next post.

-

The Film Festival Payment Debate

- Posted on 5th Mar

- Category:

Reading Sean Farnel’s recent posts on IndieWire about film festivals has been great fun. Seriously, while I disagree with some of his posts, it sure is fun to read everything he writes and he isn’t afraid to offer up an opinion he knows won’t be popular. He knocked up a bit of a shit-storm recently by re-igniting the age-old debate on whether festivals should pay filmmakers for playing their films.

“Good grief, here we go again,” all of us old farts collectively sighed. Sure and soon enough the festival blog-o-sphere raised its head and shot down the argument again. Tom Hall did a great job of laying out the economic issues faced by all fests. Heather Croal did a good job of bringing up the other value a fest brings to filmmakers, and in a brilliant comment from Nick Fraser, we got some finger wagging at some other culprits in the not-paying-the-filmmaker-enough arena (and I agree with him). Yahoo, glad we could do that again.

This argument comes up time and again. I remember my first Sun/Slamdance as head of the Atlanta Film Festival over ten years ago, when John Vanco brought up this argument, and I’m sure it came up many a time before and since. Each time, the arguments on both sides of the issue are the same, but I’m left feeling like we’re having the wrong debate altogether.

I mean let’s face it; both sides have a good argument. LGBT Fests and Jewish Film Fests are nonprofit, struggling entities and routinely pay fair fees for films they program and haven’t gone out of business. But then again, how many LGBT filmmakers do you know that are raking in the dough? On the other hand, there are many good fests that provide such a great environment for filmmakers that perhaps the filmmakers should be paying them for the opportunities they’re getting – I mean, hell, people pay a booker to put them in theaters all the time now.

But whether or not a festival can or should pay is ultimately just the first question we should ask, and then we should quickly move on to the deeper, thornier questions that might actually lead to some meaningful change.

Such as? Well, several questions, but here’s just one for today, and the answer brings up even more good questions: why have film festivals at all?

I can tell you this – many of them can’t justify their existence anymore with a straight face. That still leaves a lot of good ones who can, but having run some fests, and having studied the history of them (in the US) quite a bit, I can tell you why most of them started: Nearly every festival in the US started because it was the only way that filmmakers in X town could see the work of other indie, art-house and foreign films. It quickly grew to include the lofty mission of presenting such work to the general public in such towns, but the usual narrative was this: It’s 1975, you’re a filmmaker and you shoot film. You need to edit it, which requires a Steenbeck, so you and your buddies form a film co-op to jointly purchase and share one. You get a grant from the NEA (or its precursors) and lo-and-behold, you’ve got a little film commune going. Soon enough, you realize that it’s hard for anyone else to see your films, so you band together and start a festival where you show one another’s films, mainly to one another, and this idea slowly leads to the idea that other people might want to see these things. So you start a film festival. Others nearby do as well, and soon you are sharing film prints from Paris, France to Paris, Texas as others get the same idea and open festivals elsewhere (yes, a few started well before the 70s, but most started then).

This was laudable, and it worked. The greatest untold story of film might be just how cinema culture fed by American Film Fests led to the success of Miramax and others (and the eventual bubble and “death of truly indie film”), but that’s a story for another time. Most importantly, it was a mission that was absolutely true – without such festivals, many a town would never have seen amazing films from independent and worldwide talent, and festivals could claim that without them, their towns would be a lesser place, and that these films would not get seen.

This is no longer true.

We all know why. The Internet has come along, as well as cable VOD, Netflix and numerous other options for finding films. Smart filmmakers can build an audience there too, and a successful internet short is now measured in the millions of views, an audience about 1,000 times greater than the number of people who might see your short at a few great film festivals. Yes, I know festivals add a lot of other value too, that filmmakers love showing in front of an audience and all that jazz. Having met my wife outside the theater of a regional festival, I can definitely attest to the community building they offer as well. Trust me when I say I am not being anti-Festival when I say that the mission has been accomplished and something needs to change.

So the question isn’t whether or not festivals can pay filmmakers or even whether they should pay filmmakers. And it’s not whether or not festivals offer lots of other hunky-dory stuff for attendees. The question should be, what do filmmakers need most now? And is what they need something that a festival can help with, or do we need to start something different to solve this need? If filmmakers got together in the same spirit that led them to create film co-ops and festivals (and filmmaker organizations, and magazines, and…) then what would they make together today?

Answering these questions might ultimately be more interesting than coming back to the should festivals pay question again and again. I believe that good festivals can help with answering these questions, and will try to address more of them here soon.

One Response to The Film Festival Payment Debate

Mind Twin Media says: December 29, 2013 at 6:53 am (Edit)

If I could make something today it would be a co-op that focuses on building an audience by taking advantage of both old school and new school tactics. The wheel doesn’t need to be reinvented, it just needs to be updated.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks